Mr Erdogan, who has readily sent his army into the many-sided civil war in Syria, has also started flexing his muscles in Africa. “Turkey is known for giving a blank cheque, particularly when you’re in desperate need of economic or military aid,” says Abel Abate Demissie, who works for Chatham House, a British think-tank, in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital. These days Turkish flags adorn packages of food, schools and wells. In 2003 some 60% of Turkish aid was channelled this way.

Previously it gave money mainly through international agencies such as the UN.

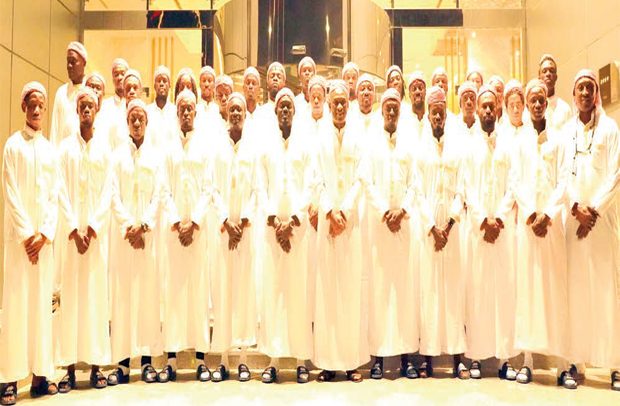

Turkey is also gaining clout through aid. Last year Tanzania awarded a Turkish firm a $1.9bn contract to build a modern railway line. Turkish officials reckon that Turkish firms have completed some $78bn worth of African projects, including airports, stadiums and mosques. So has construction, where Turkish firms are chipping away at the dominance of Chinese ones, helped no doubt by a drop in lending by China. Trade with the continent has expanded greatly, to $29bn last year, of which $11bn was with sub-Saharan Africa, an almost eight-fold increase since 2003. Turkish Airlines, which flew to only four African cities in 2004, now flies to more than 40. Ambassadorial glad-handing has helped businesses expand. In 2009 Turkey had just a dozen diplomatic missions in Africa. His visit, the first by a non-African leader in about two decades, marked the start not just of Turkey’s involvement in the Horn of Africa but of deeper ties across the continent. The turning point was in 2011 when Mr Erdogan, flanked by Turkish businessmen, aid officials and Muslim charities, visited Somalia, then in the grip of a drought and civil war. But as relations with the West have cooled, Turkey has pivoted south. Instead it looked west and dreamed of joining the European Union. Only two decades ago Turkey had very little interest in Africa below the Sahara. Somalia is a striking example of Mr Erdogan’s broader push into Africa in search of markets, resources and diplomatic influence. With its own herd of dwarf antelope and a sweeping view of the Indian Ocean, his embassy is Turkey’s biggest anywhere, too. “We are the only ones in the field,” says Mehmet Yilmaz, the Turkish ambassador. Non-Turkish companies and embassies tend to operate from the guarded “green zone” around the airport. “In Somalia one of the advantages of being a Turk is that you pray at the same mosques as everyone else,” says Kadir Mohamud, a Somali businessman. Perhaps more distinctive even than the size of Turkey’s presence in Somalia is its boots-on-the-ground approach, helped by a common religion.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)